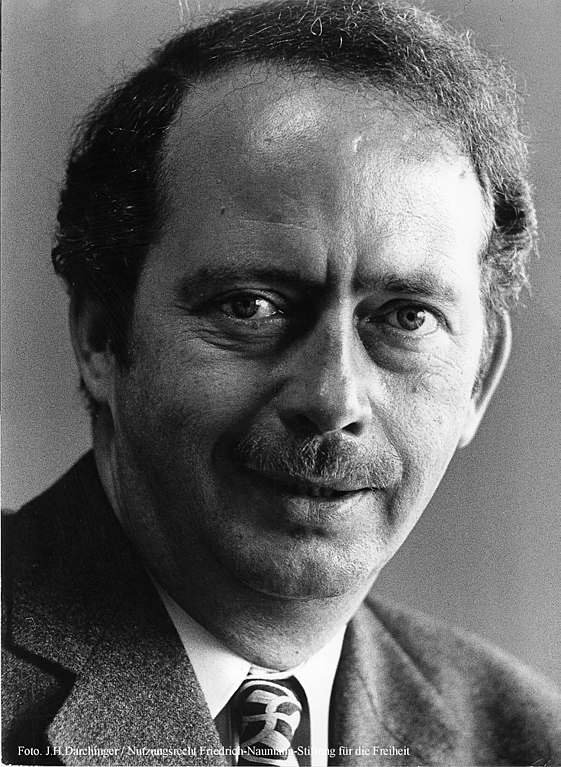

Ralf Dahrendorf Photo: J.H. Darchinger, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons Liberalism was hugely fortunate in having such an articulate and original thinker and advocate as Ralf Dahrendorf. British Liberalism was unfortunate in that he was already forty-five years of age before he came to London in 1974 - as Director of the London School of Economics. One can only speculate as to the difference he might have made to Liberal Party politics here had his influence been significant twenty or even fifteen years earlier. As it was, his political career began in his native Germany in 1968 when the Free Democrat Party under Walter Scheel was a much more radical Liberal animal than its later incarnation under Graf von Lambsdorff.

Ralf Dahrendorf Photo: J.H. Darchinger, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons Liberalism was hugely fortunate in having such an articulate and original thinker and advocate as Ralf Dahrendorf. British Liberalism was unfortunate in that he was already forty-five years of age before he came to London in 1974 - as Director of the London School of Economics. One can only speculate as to the difference he might have made to Liberal Party politics here had his influence been significant twenty or even fifteen years earlier. As it was, his political career began in his native Germany in 1968 when the Free Democrat Party under Walter Scheel was a much more radical Liberal animal than its later incarnation under Graf von Lambsdorff.

Ralf's original discipline was sociology but, although sociology certainly continued to underpin and inform his writing, politics and applied political theory were his consistent forte. His background in sociology ensured that his political ideas had a secure foundation in rigorous analysis, and his ability to see clearly the flaws in opposing arguments, and particularly in "received" thinking, was often startling in that once he had pointed out what the Liberal position should be, it tended to be blindingly obvious. I doubt that I was alone in being jealous of Ralf's clarity of mind and intellectual self confidence.

Take, for instance, his description of the Greens in The Modern Social Conflict (1988) as "a party to end all parties," based on his view that “in most cases the Greens are merely the translation of a social movement into a political organisation. The social movement responds to one of the disparities in people's social position, the threats to the environment of life. Since these threats affect everybody, a "party" to represent them is a contradiction in terms. Given the Liberals' and Liberal Democrats' consistent espousal of sustainable economics from Mill onwards, why are we not shouting Dahrendorf's analysis of the Green party at every opportunity?

Following Ralf's appointment at the LSE at the end of 1973 the BBC invited him to give the 1974 Reith Lectures. Entitled The New Liberty - Survival and Justice in a Changing World, the six lectures set out for his audience of movers and shakers a thoroughly Liberal analysis and prescription, clothed in a flimsy non-partisan sheen for the sake of the BBC's reputation. Once again the party failed to appreciate the intellectual asset available to it at a crucial political moment.

One was always struck by Ralf Dahrendorf's remarkable prescience. The Reith lectures, and his even more focussed political follow up, Life Chances (1979), were the Liberal answer to Thatcherism even before its embodiment in government. His emphasis on the liberating power of the individual's ability to grasp personal opportunities, underpinned by an enabling state, provided Liberals, had they but seen it, with both the case against Thatcherism and the reason for distancing themselves from an outworn social democracy. By November 1980 Ralf was already convinced by what he saw of Thatcher to write: "the Conservatives are trying their hardest to turn back the pages of history and will finally be crushed by their weight, but not before they crush others. The experiment is an expensive one."

Given Ralf Dahrendorf's visceral opposition to conservatism, his intellectual critique of authoritarian socialism and his early social democratic background, one might have expected him to be sympathetic to the SDP. Far from it. His most well known quote is probably that the SDP was "promising a better yesterday." The direct quote is today elusive, and Ralf himself, whilst certainly not resiling from its sentiment, could not recall its first usage. It probably comes from a somewhat similar comment in his June 1982 New Statesman review of Susan Crosland's biography of Tony Crosland.

In fact, he was scathing about social democracy, and his Unservile State Paper of March 1980, After Social Democracy, is a brilliant analysis of the impending challenge that would shortly come from the SDP. I drew a great deal from it for my own booklet a year later, Social Democracy - Barrier or Bridge? Neither of us were heeded at the time and the SDP was accorded a deference that it did not deserve despite Ralf Dahrendorf's sharp comment that "the social democratic approach to the economic, social, cultural and political problems of the day has exhausted its strength. More than that, it has begun to produce as many problems as it solves ..... Social democracy in general has ceased to be a subject of political thought, it is almost as if all the imaginative minds had emigrated to opposition groups." His conclusion was typically prescient:

.... there are no signs at all that a centre party based on the present right wing of the Labour Party will be any more forward-looking than the ruling social democratic parties on the Continent. The issue today is not how to be social democratic, much as this may agitate the victims of adversary politics. The issue is what comes after social democracy. If this is not to be a Blue, Red or Green aberration, it will have to be an imaginative, unorthodox and distinctive liberalism which combines the common ground of social-democratic achievements with the new horizons of the future of liberty.

Later in 1980 he wrote that "Increasingly it has become evident that the social democratic consensus which has enveloped the politics of the industrial world in recent decades is in itself an oppressive force which gives rise to protests and new demands."

When one turns to Ralf Dahrendorf's writing on Liberalism generally and on other key subjects such as Europe or Equality, the problem is what to leave out. One is always struck by his sensitive use of language and his vivid analogies. (There ought perhaps be a law against foreigners writing and speaking such beautiful English!) Read for instance the whole of his superb essay on Freedom in The Dictionary of Liberal Thought, (2007) and take this passage from his Reith lectures:

Improvement is about quality. This begins with small things which are nevertheless not to be discounted, because they improve the quality of our lives. The recovery of cities for people is one example: precincts for pedestrians, underpasses for cars rather than for human beings, restored old buildings rather than slums. The way people live, the space and the comforts of their homes, provides many other examples. So do the arts, the opportunities for recreation and play, sports, and whatever contributes to beauty and to pleasure.

All this, I repeat, is important for an improving society, but improvement means more. It is more than a butterfly which adds a touch of colour to an otherwise drab and hopeless world, but goes to the core of this world, that is, the social construction of human lives.

Ralf was never frightened of tackling the dilemmas that have always beset Liberal thinkers. In 1988 he gave a remarkable speech to the Liberal International Congress in Pisa in which he addressed the issue of collective rights:

For the liberal, there are no collective rights, because all collectivities need representation, and all representatives are temptable by the arrogance of power, and thus liable to take away rights rather than give them protection. Rights are settlements of individuals, and more often than not they serve to protect persons against self-appointed or self-anointed "representatives" including those who claim to speak for whole peoples.

He went on to tackle issues of sustainability and liberalism:

The surprising and worrying discovery of the 1980s is that economic growth does not by itself solve all problems. It is, at least in practical terms, not even true to say that we must have growth first and then think about redistribution; most of those who argue this way never get to the second step. The decade of wild, often thoughtless, always greedy growth has in fact raised the issue of citizenship rights for all anew. The long term poor and persistently unemployed are disenfranchised in the sense that they are not a full part of economic life, have little say in political affairs, and live at the margin of society. Liberty is indivisible. Those who accept the exclusion of some have betrayed the principle and will end in a world of privilege and oligarchy.

For me an additional gain was Ralf Dahrendorf's wide reading which, when cited in his writings, encouraged me to delve further into the authors in question. Who but Ralf would have quoted Albert Camus on the key role of art in political change?

In 1988, at the time of the merger between the Liberal party and the SDP, Ralf told me that my analysis was correct and that he agreed with it, but that he believed that I was wrong not to join the new party. He believed that there was no alternative to the merged party. His contribution to the 1996 book Why I am a Liberal emphasised the same point: "If one is active in public life, one needs a party. Being a cross-bencher may be a commendable state of mind, but it is not an effective way of taking part in debate. The party which comes closest to my beliefs and intentions is that of the Liberal Democrats. Why? Because I am a Liberal as well as a liberal." It was the ultimate irony that he apparently never joined the Liberal Democrats and that in 2004 he resigned the Liberal Democrat Whip in the House of Lords to move to the cross-benches.

For the Liberal Democrats he had in 1996 chaired the Commission on Wealth Creation and Social Cohesion, which had a debate in the House of Lords but not much other exposure. The truth was that, although he tackled both, Ralf Dahrendorf was more a Liberal philosopher than a policy writer. A broad brush man rather than one for detailed points, his confidence in the relevance of Liberalism should be a lesson for all of us today. As he wrote to me: "It really is my view that the only chance of a political theory for the future which is not a re-writing of the past, is the Liberal chance."

Ralf Gustave Dahrendorf, Baron Dahrendorf of Clare Market in the City of Westminster,born 1st May 1929, died 17 June 2009.